This is a book chapter published in the book Crossing Views – Educational Partnership between Parents and Education Staff published by RESLING Publishing (Tel Aviv, Israel) in 2022 in Hebrew edited by Itzhak Gilad and Edith Tabak.

מעורבות הורית כאזרחות פעילה- בהשראת ההתמודדות עם אתגרים באירופה ובעולם

אסתר סלמון, מנהלת ארגון ההורים הבינלאומי

Abstract

The current article is attempting to summarise challenges and solution in parental engagement for equitable, quality education to successfully address general educational challenges as well as challenges around meaningfully engaging all parents for the benefit of their children and themselves. It is based on the active citizenship and participation aspect of parental engagement for the benefit of not only one’s own child, but for the benefit of school as a community the parent belongs to. The paper combines desk research on educational challenges, trends and practices in the field of working with parents and current issues around active citizenship and citizenship education with an analysis of our own research on parental involvement and engagement in Europe partly in view of school costs that parents need to cover. Desk research was done using primary and secondary research resources, legislation, policy papers as well as position papers and guidance by international institutions such as the World Bank, UNESCO and the Council of Europe. Our own research was carried out in 23 countries (22 EU Member States and Norway) using a detailed online research questionnaire filled by invited parent leaders and policy makers with a 100% response rate. Outcomes show that meaningful participation of parents is only possible in some fields and in maximum 2/3 of all countries examined. While according to our research there is a long way to go for school leaders, teachers and parents to collaborate on transforming school and education in general for the 21st century, there are inspiring, successful practices to build on.

חומרי הרקע במאמר זה מתבססים על ניתוח מסמכים הנוגעים למדיניות, ניירות עמדה, ושותפות הורים בעיקר לעלויות הנדרשות בתשלומי הורים לכיסוי ההוצאות בבתי הספר במסמכי מוסדות בינלאומיים כמו הבנק העולמי, אונסק”ו והמועצה האירופאית..

נתוני המחקר במאמר נאספו באמצעות שאלון מקוון שנשלח למנהיגי הורים וקובעי מדיניות ב 23 מדינות החברות באיחוד האירופאי. שיעור ההיענות היה 100%.

תוצאות המחקר מראות כי השתתפות משמעותית של ההורים אפשרית רק בתחומים מסוימים ובמקסימום של 2/3 מכלל המדינות שהשתתפו במחקר. על פי מסקנות המחקר, קובעי המדיניות בבתי הספר, מנהיגי בית הספר, מורים והורים רחוקים עדיין משיתופי פעולה משמעותיים במעורבות הורים. לפיכך יש לטפח שיטות המעודדות מעורבות הורית ואזרחות פעילה של ההורים ולהתאימם לאתגרי ההתחדשות של בתי הספר והחינוך במאה ה -21.

.

Challenges in education that require parental engagement

The world is facing a global learning crisis (World Bank 2018.) that has a number of surprising, but shocking characteristics. It is not only about children with no access to school anymore, but abut those who do attend formal education, even receive some kind of school leaving certification, but do not acquire basic literacy and numeracy skills, not to mention other skills necessary for the 21st century. School has little to do with real life which is a multifaceted phenomenon. First of all school curricula are often overcrowded with skills and academic content that is outdated and without consensus on why they are necessary to teach and learn. School is also often sheltered from the outside world meaning that it provides little support and skills development in the field of everyday life situations – present and future – especially for those whose parents are less able to provide such necessary education at home struggling with aspects of everyday life themselves.

At the same time, there is a consensus that there is a need to change as quality, inclusive education is one of the keys to sustainable development all over the world. This is defined in the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), and education has a highlighted position being given number 4 as an SDG. (United Nations 2015.) There is also a growing consensus on the changing role of school and education that necessitates a change of approach from educating obedient workers for the assembly line to educating creative, critical thinkers for a robotised world.

By now there is a full consensus about the fact that meaningful learning is not confined to schools (rather real learning often only happens outside of school), while nearly all countries are still trying to find ways to acknowledge, build on, evaluate and certify learning happening in nonformal and informal settings. In 2015 the UNESCO published Rethinking Education calling for the world to change its approach to the organisation and governance of education based on treating it as a common good rather than a public one. It is a major move towards not only re-thinking, but also co-thinking about education. Education as a common good implies that the state is still responsible for offering adequate financial provisions for education as all countries are obliged to do so by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), but the organisation and evaluation of education is based on an active citizenship approach, understanding that quality education is the responsibility of all, but it also makes a lifelong learning mindset necessary as everybody in this framework is a learner and an educator at the same time.

Role of schools in engaging parents and children in finding the solutions

The above global demands make It necessary for the teaching profession to change and for teachers to see themselves as facilitators of learning and not as sources of knowledge anymore. This change also means that teachers should understand and prepare for their role in supporting parenting and supporting parents in general to become better educators of their children as well as more active citizens, starting from school contexts. This also requires a lifelong learning mindset on the teachers’ side, an urge to constantly develop their professional knowledge and skills.

It is of crucial importance that school should open up on the one hand allowing education provisions to be linked with real life challenges – not restricting it to immediate labour market needs, but the necessity to educate responsible 21st century citizens who understand how to navigate in current and future realities – that means inviting external players into the classroom and the school in general. On the other hand, ‘school’ needs to leave the building and provide guided learning opportunities for their students as well as the community in venues like parks, community centres, businesses or even homes. A high number of inspiring practices have been collected on open school practices in the Open Schools for Open Societies Horizon2020 project that Israel participates in. Its little sister is Open School Doors that provides teacher training and methodology support for teachers in engaging parents, especially disadvantaged ones. An open school approach looks at parents as resource, a key to find the right solution to the above-mentioned challenges. Considering parents as a resource must not be limited to highly educated parents, this is why teachers need training in working with parents below their own socio-economic status level. Research done in the Open School Doors project (Kendall et al. 2018.) clearly shows that teachers lack skills and knowledge in this field. At the same time teacher training provisions in the field – be it initial teacher education or continuous professional development (CPD) – are scarce in nearly all school systems. School systems with Anglo-Saxon traditions, such as the UK and Ireland, are clearly in the lead in this field.

There is a need to mention two factors beyond teachers in establishing parental engagement practices and finding solutions for the need to change schools. Legislative frameworks should be in place that makes it necessary for schools to engage parents and also the students themselves in all procedures. There are countries that regulate student and parent representation in main decision-making bodies, soch as school boards. Other systems oblige the school to seek the opinion of parents (and students) and in certain topics (eg. choice of school books, time of holidays, election of school head) the school’s decision is not valid without such an opinion. Some countries give parents (and students) veto rights in certain areas… This in itself will not ensure meaningful participation. An extensive research done in 23 European countries on participation (Salamon-Haider 2015.) clearly uncovered a pattern that it only provides for structures and thus participation is often restricted to formalities. This is a dangerous trend as schools that only wish to tick the boxes will find ways to involve ‘tame’ parents, resulting in representation of white middle class only in decision-making structures.

This is the reason why the other important factor is the school leader / principal in implementing inclusive participatory structures at school level. Research (Salamon-Haider 2015.) shows that there is no school system in Europe that forbids school leaders to engage parents and students, so inclusive participatory practices can be implemented even in systems where there is no legislative requirement for that. An equally important task for school leaders is to change existing practices in school boards, parent committees and similar structures to provide engagement opportunities for all students and teachers. It depends on the school leader most of all if existing formal structures become meaningful or not. For a short period of time the driving force behind such changes can be a small group of committed parents, but for lasting changes the school leader needs to take a lead in this field, too. According to very recent research (Kelly 2019. and Salamon 2019.) school heads understand the importance of collaborating with parents and engaging students, but they have little professional help in doing so. Ken Robinson in his 2018 book You, Your Child and School provides inspiring practices, mostly from the United States, but he also makes it clear that there are no recipes, local solutions must be found understanding the context of that given school, and thus it is the task of the school leader.

Parental engagement and student participation are practical examples of active citizenship, and a perfect training field for present and future active national or global citizens, where they can experience and experiment at a low risk environment. Teachers also need to look at engagement as active citizenship practice and support their students and their parents in it. Often, teachers need to approach their own active citizenship as a field where they need more conscious approaches and even training. In short, teachers also need to be active citizens of their school. Parent-teacher-student collaboration is also a good opportunity to experience the impact of non-participation, opting out, but also to learn that active citizenship includes active bystandership. Thus, parent engagement and student participation are very closely linked with citizenship education – and this link needs to be made clearly for all.

Current approaches to citizenship education

Citizenship education is one of the areas identified as important by all critiques of current education systems. However, there is no consensus on how provisions are to be organised and how to identify learners and educators in this domain. Recent developments in the world clearly show that even in countries with a long-standing democratic tradition have serious knowledge and competence benefits in this field in the general population (Harari 2018., Snyder 2018.) So far the prevalent approach to citizenship education has been the inclusion of the domain in the curriculum, and thus creating the framework for learning ABOUT citizenship and democracy.

Parents organisations in Europe have demanded a learning by doing approach (EPA 2015.), to make it part of school culture. In an ideal case citizenship education starts at a very early age, at home, but given the general levels of democratic practices schools need to play an important role here. As it is not only students who need to embrace this culture of democracy, school has a responsibility to educate parents and teachers in this field (Robinson 2018.). Meaningful engagement in decision making is an important tool for this. Becoming responsible citizens can be a natural process that can be systemised and structured as a knowledge and skills set later in school life for all students. Israel has a well-established tradition of democratic schools, but in most cases these schools only engage students themselves in school decision-making. While it is a major achievement, the engagement of parents is also an imperative.

For definition’s sake, let us identify the most important features of democracy. Contrary to general belief and colloquial discussions about it, democracy is primarily not about freedom, but trust and responsibility (Harari 2018.) The general discourse usually focuses on active citizenship, and when it comes to day-to-day practices it discourages many that they do not wish to become candidates in elections, they don’t generally take action in most situation. In citizenship education we have two major tasks that need to be highlighted as often neglected areas, but ones that schools can easily offer experience in for students, but also for teachers and parents. One is that school is a safe environment to experience citizenship, including experiencing the consequences of opting out of decision-making. Another field is the education towards and appreciation of active bystandership. Active bystanders are aware of news, trends, event, their active citizenship may not exceed exercising the right to vote, but they are conscious that there might be instances when they need to become active, eg. by participating in a demonstration or boycotting a product.

In an ideal case both parents and teachers act as trainers, counsel for students in becoming active citizens. The key is to trust in children from an early age, but not overburdening them with decisions and helping them making informed choices the consequences of which they have to live with. My personal favourite example of early citizenship education is when your 2-year-old insists on having lemon ice cream. You know he does not like it, you advise him to opt for chocolate, his favourite, but if he insists on lemon, you buy it and – this is the key for citizenship education – make him eat it regardless the tantrum thrown.

In the past decade or so citizenship education started to focus on citizenship in the digital age or active digital citizenship. It is the Council of Europe that has done substantial work in the field with recommendation for promoting the development of digital citizenship education being developed by a working group I am a member of. It is expected to be adopted by the Council of Ministers at the beginning of 2020 latest.

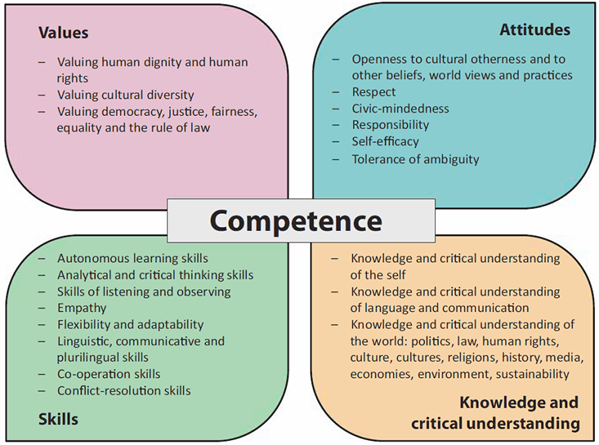

It builds on the work of academic experts such as Janice Richardson, Sonia Livingstone and Brian O’Neill and tackles the need for education un 10 digital citizenship domains. The 10 domains are grouped into 3 areas: Being online (related domains: access and inclusion, learning and creativity, and media and information literacy), Well-being online (related domains: ethics and empathy, health and well-being, and e-presence and communication) and Rights online (related domains: active participation, rights and responsibilities, privacy and security, and consumer awareness) Our Council of Europe expert group also defined the necessary competences for democratic culture in order to safely navigate the 10 domains. This is represented in the butterfly below. It should be obvious for the reader that on the one hand these competences need to be developed in and outside of school, but also that the overwhelming majority of both parents and teachers need competence development for becoming active digital citizens of the 21st century.

The benefits and types of parental engagement with schooling

The role parents in developed countries are expected to play in their children’s schooling has changed significantly over the past 20-30 years expecting parents to be engaged acting as “…quasi-consumer and chooser in educational ‘marketplaces’” and “monitor and guarantor of their children’s engagement with schooling” (Selwyn 2011). Research evidence (Harris and Goodall, 2008, Desforges & Abouchaar, 2003) also shows it clearly that parental involvement results in better learning outcomes and school achievements for young people. This makes it imperative to involve parents in schooling and this approach has gained widespread political traction in many European countries.

However, defining what is meant by parental involvement/engagement in schooling, the kind of interactions and methods most likely to benefit children, the role and responsibility of players, especially that of parents, teachers and school leaders, remain somewhat complicated. Politicians, researchers, schools, teachers and parents’ groups and children are yet to settle on shared definitions or priorities that sometimes lead to confusion. Although often presented as a “unified concept” parental involvement/engagement “has a range of interpretations, which are variously acceptable or unacceptable by different constituents” (Crozier, 1999). Different stakeholders often use this fact in a way that leads to power struggles and tensions between different stakeholders, and sometimes also lead to some kind of a ‘blame game’. As Harris and Goodall’s 2008 study of parental interaction in schools illustrates, whilst parents were more likely to understand their involvement as support for their children and children, in turn, saw their parents as ‘moral support’, teachers viewed it as a “means to ‘improved behaviour and support for the school’” (Harris and Goodall 2008). This may lead to a void between expectations of schools towards parents and vice versa.

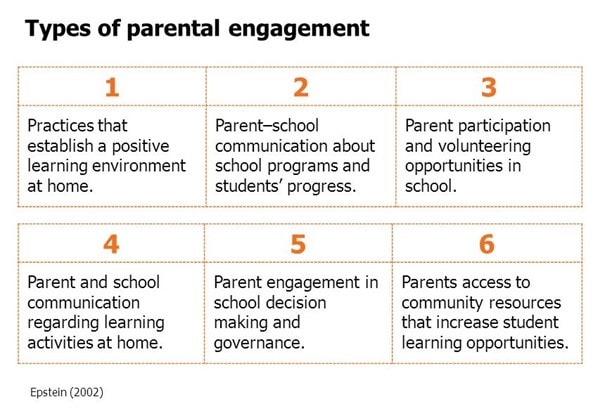

Epstein’s (2002) classification has been widely used in establishing a typography for parental involvement with school. It is important to take note of the fact that Epstein goes beyond the notion of involvement or engagement in learning of the individual child, but rather introduces the notion of partnership schools that are governed based on a mutual, balanced appreciation of home and school that has a major impact on establishing participatory leadership structures. This definition is the fully in line with our approach to tackle parental engagement as active cizitenship. Epstein’s Framework defines six types of involvement, parenting, communicating, volunteering, learning at home, decision making, collaborating with the community. It is important to state that these types have no hierarchy whatsoever, although they are often seen by some schools and teachers as levels of different value and formulating unfounded expectations towards parents whose need for engagement is different (Hamilton 2011.)

Goodall and Montgomery (2013) have argued for an approach that moves interest away from parents’ interactions with school generally and back to a more specific focus on children’s learning. They make a key distinction between involvement and engagement suggesting that the latter invokes a “feeling of ownership of that activity which is greater than is present with simple involvement” and propose a continuum that moves from parental involvement with schooling to parental engagement with children’s learning. This approach includes the recognition that learning is not confined to school and the importance of supporting the learning of children inside and outside school. This approach can be particularly important in the case of parents (and of course children) from ethnic minorities, with low levels of education (and bad experiences with their own schooling) or those facing economic difficulty who, research has shown, are more likely to find involvement in school difficult but who nevertheless have strong commitments to their children’s learning.

Goodall (2017) urges for a paradigm shift towards a partnership that is based on the following principles formulated on the basis of reimagining Freire’s banking model of education for the 21st century’s reality:

1. School staff and parents participate in supporting the learning of the child

2. School staff and parents value the knowledge that each brings to the partnership.

3. School staff and parents engage in dialogue around and with the learning of the child

4. School staff and parents act in partnership to support the learning of the child and each other

5. School staff and parents respect the legitimate authority of each other’s roles and contributions to supporting learning

This approach is also in line with the distinction made between involvement and engagement with regards to school in general, especially with regards to ownership. In the classification traditionally used by parents’ association (Salamon 2017), based on Epstein, parental involvement in school means that the school and teachers initiate that parents join certain activities that are mostly aiming at the better working of current structures of school, while engagement is based on the partnership principles and implies that the school leader, teachers, parents, students and, if necessary, other stakeholders jointly take action for establishing practices and procedures based on the initiative of any of them. In this framework of definition parental involvement in school corresponds to the tokenism levels (informing, consultation and maximum placation) while parental engagement with school corresponds to citizen power levels (partnership, delegated power or citizen control) on the Ladder of Participation (Arnstein, 1969).

The two approaches, engagement with children’s learning and engagement with school has the common feature of ownership, and with time parents active citizens should become active bystanders even if only focusing on children’s learning, having enough insight to act as active citizens if a situation making intervention necessary arises.

According to Kendall et al. (2018) these frameworks acknowledge the complex, dynamic nature of relationships between parents, school and children and offer open meaningful opportunities for dialogue and re-negotiation of roles and responsibilities, but they may not go beyond questioning traditional paradigm of home-school relations. Re-imagining home-school relations need to be based on reflection on the purpose of learning, of school and going beyond the immediate and often narrow priorities based on testing and other policy accountabilities (Grant, 2009). Grant goes on to suggest, many parents may choose, quite reasonably, to invest in insulating the boundaries between school and home life seeing “part of their role as protecting children from school’s incursions into the home and ensuring that children socialise, play and relax as well as learn”, and this is the underlying thinking in home-schooling and unschooling movements gaining momentum (Robinson 2018). This also gives us reasons to explore reasons of non-involvement or low levels of involvement with schooling when designing any intervention on parental empowerment and reimagining parental engagement as active citizenship. This is a result of the above-mentioned phenomena in the global learning crisis (World Bank 2018) that requires a paradigm shift engaging parents in the rethinking process. The only way to ensure equity and inclusion in school is to co-create an offer that answer correspond to and reflect on the needs of each individual child.

Working with ‘hard-to-reach’ parents

The term ‘hard-to-reach’ has often been used to ‘label’ and pathologize “parents who are deemed to inhabit the fringes of school, or society as a whole—who are socially excluded and who, seemingly, need to be ‘brought in’ and re-engaged as stakeholders (Crozier and Davis, 2007). Although the label has been discussed and tackled in recent literature and practice, it remains an enduring concept in policy and practice discourses in Europe (Hamilton 2017:301). Campbell (2011) defines ‘hard to reach’ parents as those who: “have very low levels of engagement with school; do not attend school meetings nor respond to communications; exhibit high levels of inertia in overcoming perceived barriers to participation” (2011:10). The term is often used to refer to parents who fail to reproduce the attitudes, values and behaviours of a ‘white middle class’ norm described in Deforges above, which, argue Crozier and Davies (2007), underpins consciously or unconsciously, school expectations.

Goodall and Montgomery (2013) discuss the situation of parents who are often ‘labelled’ as ‘hard-to-reach’ because school may not yet have facilitated an appropriate or effective way of building relationships with them. Findings from the Engaging Parents in Raising Achievement Project (EPRA) indicated that for some parents, often those characterized as ‘hard-to-reach’, schools, especially secondary schools, can be experienced as a “closed system”, as hostile or disorientating, due perhaps to the parent’s own experiences of school or wider structural relations that they may feel position them negatively in relation to the ‘authority of school’ (Harris and Goodall, 2008).

Bursting myths around impactful engagement

Deforges’ (2003) systematic review of the positive impact of parental involvement on children’s school attainment establishes the degree of significance of this topic. He found that whilst parents engaged in a broad range of activities to promote their children’s educational progress (including sharing information, participating in events and school governance) degree of parental involvement was strongly influenced by social class and the level of mothers’ education: the higher the class and level of maternal educational qualification the greater the extent and degree of involvement. In addition, the review also noted that low levels of parental self-confidence, lack of understanding of ‘role’ in relation to education, psycho-socio and material deprivation also impacted negatively on levels of participation in school life with some parents simply being “put off involvement by memories of their own school experience or by their interactions with their children’s teachers or by a combination of both.”. The review concluded that whilst quality interactions with school (for example information sharing and participation in events and governance) are characteristic of positive parental involvement in education, a child’s school attainment was more significantly bound up with a complex interplay of a much broader range of social and cultural factors, including “good parenting in the home…the provision of a secure and stable environment, intellectual stimulation, parent-child discussion, good models of constructive social and educational values and high aspirations relating to personal fulfilment and good citizenship. Identifying ‘at-home good parenting’ as the key factor in determining children’s attainment the review found that this form of involvement “works indirectly on school outcomes by helping the child build a pro-social, pro-learning self-concept and high educational aspirations” and had a much greater impact on achievement than the effects of school in the early years of schooling in particular. Grouping these factors together as ‘spontaneous parental involvement’ the report reviewed various interventions that aim to enhance engagement. Interventions included parenting programmes, home-school links and family and community education, the review was not able to find a positive correlation between these activities and attainment data and suggested they were “yet to deliver the achievement bonus that might be expected.”

Price-Mitchell (2009) highlights an over-emphasis on school learning as the only, or priority, objective of home/school interactions. As such schools offer a ‘mechanistic view’ which separates educators and parents rather than connecting them with “educators see[ing] themselves as experts” in children’s learning “rather than equals”. According to her this creates hierarchical relationships and limits capacity to understand and develop partnerships that create new knowledge. Mitchell-Price also pays attention to the way that social capital circulates within the context of school and its potential to include or exclude parents from different social and cultural groups.

European policies on parental involvement

Several reports and studies (eg. OECD 2012, MEMA 2017) confirm that significant obstacles still exist in the educational pathways of children with a disadvantaged background in the educational systems of the EU Member States. This is accompanied by an increase of intolerance and xenophobia in most EU Member States.

At the same time successful, mostly local or municipality-level initiatives show that there are effective solutions for these issues that are best tackled together. Some countries have implemented effective national policies for inclusion in education (eg. Austria, Germany, Ireland), but none have introduced a systemic approach to vulnerable parents’ inclusion.

Research on parental participation in Europe

The research carried out in 23 European countries (22 EU members and Norway) by my colleague, Brigitte Haider and myself was originally aiming at finding correlations between the direct costs of education (costs not covered from taxpayer sources, but burdening family budgets directly) and the legislative provisions related to the participation of parents in decision making related to school activities and processes with some focus on decisions that have a direct impact on family budgets. While the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union reinforces the UNCRC regulations by obliging EU member states to offer education free, there is no country among those we worked in that has these provisions in place.

The first part of our research focused on school practices and school cost realities, so they do not reflect on legislative provisions. In the second part of the research we also examined legislative frameworks and their implementation on decision-making levels. This may mean the level of government or the level of a region or municipality, respondents were asked to refer to the level where decisions are made in their countries. As this greatly varies in countries in Europe, this was the most meaningful way of asking our research questions. Respondents were experienced parent representatives and policy makers with a solid understanding if the situation in their school and country.

Methodology

The research was done using two separate questionnaires, one on school costs and one on parental engagement/involvement in decision making. These were sent to national parent organisations in the target countries, and they were invited to provide answer based on their national realities. All questionnaires were followed up, thus we managed to receive answers for all countries we wanted to include. The subjects were asked to detail their answer so that we could differentiate between school levels and types. We also collected as much legislation text translated to languages we speak (English, German, Hungarian) as possible, and during the analysis phrase we also double-checked answers whenever it was possible with legislative texts.

For the school costs research, we worked together with the European School Student Union, OBESSU and some experienced parent leaders to cover all costs that are school-related. By this we meant such costs that do not normally occur if a child does not go to school but compulsory/absolutely necessary if they do. This includes school material (books, stationery, etc.), special clothing (for sport, for hands-on activities, uniforms), parental financial contribution to school activities (eg. entrance tickets, room rent), costs of school activities that fall on parents (eg. photocopying), necessary extra tuition and getting to the school. Putting together this questionnaire happened with the participation of parents with experience at different school levels and countries.

For parental involvement, we were interested in the first place in how the voice of parents is delivered in all aspects of school life given that parents are the ones schools are accountable to and whose needs should be taken into consideration. At the same time, we were also exploring how parents are involved in decisions about schooling and schools, at legislative and budgetary levels. While most of the questions were objective, and were verified through analysing legislation, we were also interested to have the opinion of parents whether a legally regulated involvement form is a meaningful one (meaning that decision makers actively seek and rely on parent opinions) or if it is a formality (meaning representatives, often chosen by the school leader from among the “tamest” parents tick the box by having a representative present, but do not actively encourage meaningful input)

In the analysis phase, we cross-referenced the two questionnaires, making separate analyses for different school levels and types (pre-primary/primary/lower and upper secondary; state/church/private). We also took it into consideration if schooling at the given level is compulsory in the country or a choice of parents how they educate their children. We were also interested to see cultural patterns, similarities and differences depending on schooling traditions, and our assumption that this is a factor was verified by the research.

Research outcomes

It is interesting to note that while 58% consider school to be free in their countries, and in-depth analysis has shown that in reality the case is very far from it. While it is school budget that parents have the highest percentage of say in with 56% having consultative and 16% decisive role, when it comes to the choice of teaching material (books, tools, etc.) only 32% is consulted and 8% has an impact on decisions. At the same time 75% of parents pay directly for compulsory stationery, 42% pay for workbooks and 17% for coursebooks. 29% of parents have to pay directly for material for practical activities such as special paper, wood, metal, 67% are obliged to buy necessary IT equipment from family budgets that also needs investment in 63% of the cases on software. There is no country where compulsory sport equipment is not paid from family budgets and 2/3 of parents also pay directly for other kinds of working and protective clothes. These percentages show the total of parents that surely pay themselves, for others there are local provisions to a certain extent, so school costs largely depend in many countries on where you live. These high numbers should indicate that parents are involved in decision making, but practice does not prove this requirement.

When it comes to active participation in decision-making, the other area where parents are mostly involved is creating school rules with 28% having decision-making powers and another 52% are consulted. It seems that parents are considered to be competent with regards to school meals in most countries, so 60% are consulted and another 8% also has decision-making powers. However, while parents are mostly involved in this field, only 50% pf parents pay for meals.

The picture is less bright when it comes to professional matters in education. Only 8% of parents have decisive power over curriculum and 4% over teaching programme contents with 40% and 36% respectively are consulted. In only 20% of the cases parents are even consulted in the recruitment, evaluation and dismissal of teachers, while 8% have decision-making powers and 32% are consulted when recruiting or dismissing the school leader. Our research was conducted in 2015 in 23 countries, but the same trends were reported in the research on careers of teachers and school leaders in the European Education Policy Network (Kelly 2019. and Salamon 2019.)

When it comes to school student representation, it is present to a certain extent in 19 of the 23 countries and only in secondary schools in the other 4 (Netherland, Spain, Liechtenstein, Slovenia), but our research did not go into detail about their extent and form. Student representation is only present in 3 countries up to national level and a total of 7 countries up to municipality level. In only 28% of respondents reported proportionate representation of key stakeholders (parents, teachers and students) in decision making related to school in general (Hungary, Austria, Germany, Norway, Netherlands, Lithuania, Estonia) .

On the level of government in 60% of the cases there is no parental representation on government level, and even if there is, it is not equal and proportionate. This was reported in only 32% of cases. In 56% percent of the cases the government is not obliged to involve parents and other stakeholders in decision-making, and in 52% of the cases parents are not consulted about the financing of education. Only 8% of countries offer decision-making powers to parents in relation to national curricula and another 50% is consulted in some form. When it comes to the organisation of the school year and defining school holiday times, 52% of countries do not even consult parents, while 12% of countries offer parents decisive power in this with 4% of them giving parents the right to veto. Overall, 48% of governments are obliged to involve parents in decision making in some areas, but only 24% of respondents reported meaningful participation, the other 24% is just a formality.

Looking at the full picture it is not only clear that schools and governments don’t find it important to consult parents in issues that directly concern them, but it is also clear they do not understand the importance of parental involvement and engagement as a form of active citizenship.

Research done at the same time in Israel (Schaedel et al. 2015) shows similar patterns in Israel.

Inspiring European practices in the field of parental inclusion

All successful projects and initiatives in the field of parental involvement include an element that helps to overcome language/vocabulary barriers and also support inclusion of the parents themselves in society. However, successful, long-term engagement programs often build on the acceptance of differences in languages and culture made visible in school settings.

Another type of program that is in place in many local contexts is aiming at raising cultural awareness and create mutual understanding by that. Inviting parents into school settings to introduce their home cultures create more trust in school. This is especially important in the case of parents who have low levels of education themselves. It is often necessary for school staff to leave their comfort zone and the school premises for successful outreach to parents with migrant background.

The most successful and sustainable programmes (e.g. SEAs or Schools as Community Learning Centres) tackle the whole community as one, consider language and cultural differences, but offer a holistic solution.

There are two main aims of parental involvement/engagement that were explored in inspiring practices and related literature. One is the engagement of parents in the learning of their own children for better learning outcomes, the other is engagement in school life as a form of active citizenship. The second, broader approach necessarily includes the first one, parents engaged is school life also understand the importance of learning and support their own children more. At the same time, it must be mentioned that deeper engagement in your own children’s learning can be successful without more engagement in school, especially if the intervention is aiming at parents’ understanding of learning processes, their role as primary educators and the fact that school plays only a minor role in the learning of children.

Inspiring practices in some cases focus on a certain narrow target group, for example parents of a certain nationality or level of education, while others have a more holistic approach, targeting all migrants or all parents that are generally difficult to reach and engage. Inspiring practices collected during the needs analysis period show that successful models are transferable from one target group to the other, e.g. Roma programmes and migrant-centred ones often use very similar methodologies.

Recommendations and methods developed in Includ-ED as well as FamilyEduNet, building on methodology developed in the Include-ED project and partnership school’s methodology offer a useful universal source that OSD can build on. It supports an approach, where all interested parties participate in designing and implementing inclusion activities. It tackles both sides of parental engagement – in learning and in school life.

Parent Involvement 3.0 is a useful general handbook to help teachers and school heads understand the importance and possible tools of parental involvement. The methods suggested can be implemented by school leadership even in systems, where school autonomy is on a low level.

Schools as Community Learning Centres is an initiative that is very much in line with current polity trends, but implementing it needs full school autonomy and a school leader committed to it. However, even individual teachers may be able to implement certain aspects building on local community.

A simple assessment tool on parental involvement developed by NPC-p, Ireland can be used for awareness-raising as well as monitoring development in practice.

ParentHelp trainings show that its activities are equally useful for parent leaders, teachers and school heads to understand parental involvement/engagement, embrace diversity and be able to manage challenges.

Bibliography:

Arnstein, S. R. (1969) “A Ladder of Citizen Participation,” JAIP, Vol. 35, No. 4, July 1969, pp. 216-224

Campbell, C. (2011) How to involve hard-to-reach parents: encouraging meaningful parental involvement with schools National College for School Leadership: London https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/340369/how-to-involve-hard-to-reach-parents-full-report.pdf

Crozier, G., & Davies, J. (2007). Hard to reach parents or hard to reach schools? A discussion of home-school relations, with particular reference to Bangladeshi and Pakistani parents. British Education Research Journal , 33 (3), 295-313.

Cummins, J. (2003). Challenging the construction of difference as deficit: Where are identity, intellect, imagination, and power in the new regime of truth. Pedagogies of difference: Rethinking education for social change, 41-60.

Desforges, C. and A. Abouchaar (2003). The Impact of Parental Involvement, Parental Support and Family Education on Pupil Achievement and Adjustment: A Literature Review, Department of Education and Skills.

EPA Manifesto 2015 https://euparents.eu/manifesto-2015/

Epstein, J. 1992. “School and Family Partnerships.” In Encyclopedia of Educational Research, edited by M. Alkin. New York: MacMillan.

Epstein, J. 2009. School, family and community partnerships: Your handbook for Action. California: Corwin Press.

Epstein, J. L., Sanders, M. G., Sheldon, S., Simon, B. S. Salinas, K.C., et al. (2009). School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Essomba, M. et al. (2017) Migrant Education: Monitoring and Assessment. EPRS, Brussels

Fundamental Rights EU Charter

Goodall J. (2017) Learning-centred parental engagement: Freire reimagined, Educational Review

Goodall, J. (2017) Narrowing the achievement gap: Parental engagement with children’s learning, Routledge, London and New York

Goodall, J. S., (2016) Technology and school-home communication in International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning Vol 11 no 2 118-131

Goodall, J., Montgomery, C. (2014) Parental involvement to parental engagement: a continuum, Educational Review, 66:4, 399-410.

Goodall, J., Vorhaus, J. (2011) Review of best practice in parental engagement: Practitioners summary. London: DfE

Goodall, J., Weston, K. (2018) 100 Ideas for primary teachers: Engaging parents. London, Bloomsbury Education

Harari, Y.N. (2018). 21 Lessons for the 21st Century. Spiegel&Grau, New York

Harris, A. & Goodall, J. 2007. Engaging Parents in Raising Achievement. Do Parents Know They Matter? University of Warwick. Online: http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/research/data/uploadfiles/DCSF-RW004.pdf

Kelly, P. (2019). Teacher recruitment, retention and motivation in Europe, EEPN, Utrecht

Kendall, A. et al. (2018). Engaging migrant parents using social media and technology, Technical University of Dresden

National Council for Special Education, Ireland. (2011) Inclusive Education Framework. A guide for schools on the inclusion of pupils with special educational needs. https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/InclusiveEducationFramework_InteractiveVersion.pdf

OECD. 2010b: Education at a Glance 2010.

Open School Doors website http://opendoors.daveharte.com/

Open Schools for Open Societies website https://www.openschools.eu/

Pena, D. C. (2000). Parent involvement: Influencing factors and implications. The Journal of Educational Research, 94(1), 42-54.

Price-Mitchell, M. (2015.) Tomorrow’s Change Makers: Reclaiming the Power of Citizenship for a New Generation, Eagle Harbour Publishing

Robinson K.- Aronica L. (2018). You, Your child and School. Vintage, New York

Salamon E. -Haider B. (2015). Parental involvement in school and education governance, EPA. Brussels

Salamon E.-Haider B. (2015) School costs burdening families in Europe. EPA, Brussels

Salamon, E. (2017) European Schoolnet Teacher Academy

Salamon, E. (2019) Good practices in teacher and school leader career pathways in Europe from a practitioner and parent perspective, EEPN, Utrecht

Schaedel, B., Eshet, Y., Deslandes, R. (2013) Educational Legislation and Parental Motivation for becoming Involved in Education: A Comparative Analysis between Israel and Quebec-Canada. International Journal about Parents in Education 2013, Vol. 7, No. 2, 107-122

Schaedel, B., Freund, A., Ataiza, F., Hertz-Lazarowitz, R., Boem, A., Eshet, Y. (2015) School Climate and Teachers’ Perceptions of Parental Involvement in Jewish and Arab Primary Schools in Israel. International Journal about Parents in Education 2015, Vol. 9, No. 1, 77-92

Snyder, T. (2018). The Road to Unfreedom. Tim Duggan Books, New York

Tulowitzki, P. (2019) School leader recruitment, retention and motivation in Europe, EEPN, Utrecht

United Nations (2019). The Sustainable Development Goals Report. United Nations, New York

World Bank. (2018.) World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education’s Promise. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1096-1 Rethinking education